One enduring belief held by many dairy folks is that farm gate milk prices go up and down...but consumer prices only go up, with processors making out like bandits on the difference. Is that true?

I sometimes think we should have big signs for the price of milk posted on local streets so that, like gas prices, we could watch them go up and down over the course of a year or season. It would be interesting to watch if they all magically changed to the same number on a particular morning. Regardless of that, we are all well aware that gas prices go up and down, and that they are driven in no small part, albeit not entirely, by the going price for a barrel of oil.

Grocery stores and other customers of a fluid milk plant pay a wholesale price that is not regulated by the government but is certainly influenced by the Class I price that drives far and away the biggest part of a processor’s total costs. And, of course, when we are consumers, we pay a retail price that is also unregulated and subject to competition among retailers for our business.

What do the numbers say?

In the discussion below, I am going to use data from the Northeast Federal Order (No. 1) and New York. Data from other locations would not show different results, but I thought it would be better to use data for a particular location than to look at some kind of national average that intermixes prevailing U.S. and federal order numbers more than is necessary.

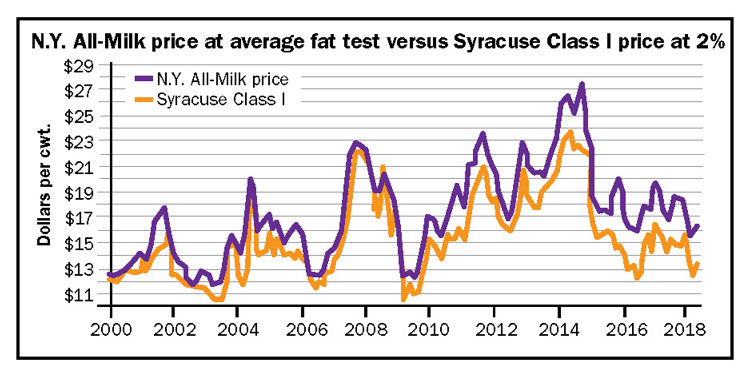

The figure shows the Class I price for the Northeast Order adjusted to the Syracuse zone (a medium-sized city in central New York) and for 2 percent milkfat test. Two percent would be an approximate average for a fluid milk processor. This Class I price is compared to the average price that plants pay for milk from New York farmers, the so-called All-Milk price, which is collected at average fat test.

What stands out first in the figure is that the Class I price is not higher than the All-Milk price. This is almost entirely a reflection of the fact that the Class I price is for a much lower fat content. What I would like to draw your attention to is that the two prices, though having a similar pattern, do not show the same ups and downs. Plus, the magnitudes of the differences vary quite a bit over time.

In fact, the relationship has changed significantly since the middle of 2010. Prior to that point, the range in the difference between these Class I and All-Milk prices ranged from $4.55 lower to $1.31 higher. Since July 2010, the range moved down to $5.23 lower and a negative 33 cents on the high side.

Beyond the general effect of high milkfat values, note that the relationship between the two prices is highly variable, changing by significant amounts, up and down, quickly. What this means is that changes in the price of milk that farmers see on the top of their checks don’t match very well with the monthly changes in the cost of milk for a Class I processor. It is entirely possible, that in any particular month, they can move in opposite directions.

What about retail prices?

A number of studies have looked at how retail prices for beverage milk changes in relation to either the cost of milk for processors or the pay price to farmers. These studies consistently indicate that:

- Retail prices do move both up and down in response to changes in the Class I price.

- The changes tend to be faster and larger on the upside than on the downside.

- Retailers will respond more vigorously to changes that are large and/or swift.

- Retailers typically employ a pricing practice called smoothing where small fluctuations in wholesale prices are largely ignored.

- Price smoothing means retailers absorb some of the upside of price to shield customers from the impact and then make up the difference on the downside.

- Regardless of the average price at any moment, retailers routinely have one or more milk products on special to attract customers to their store that week.

- Milk, even on special, is not sold at a loss.

Let’s dig deeper into that last point. The pricing of milk between stores is highly competitive. As a general rule, the gross margins on milk are less than storewide averages for other products. On the flip side, the profitability of milk remains higher than the store average because the costs of handling have been minimized and the product turnover is very high.

Bottom line

Beverage milk sales are impacted by many factors. In my opinion, there are far more influential actors than the price of milk, including diet and health perceptions, the availability of alternative beverages, and demographic changes over time.

Contrary to what is often suggested, a failure to pass along lower prices to consumers is not a reason. Retailers pass along price cuts and to some extent this helps sales. Interestingly, high butter or milkfat prices have done even more to lower the cost of beverage milk going into stores.